Game Changing: Is Your Program a Game Changer? Mine too!

Our guest columnist for this edition of “The Emperor’s New Concept” is Commander Keith “Powder” Patton, USN.

Just google it. “Game changer military weapon” links to articles from National Interest, Washington Times, The Heritage Foundation, and a host of other sites. One can think of historical “game changing” weapons: chariots, the English long bow, gun powder, steam power, armored warships, machine guns, submarines, radar, nuclear weapons, ballistic and cruise missiles, precision guided munitions, stealth, and now the potential of drones, cyber and microwave weapons. Military history seems to be full of examples, and the press and defense industry eager to promise more. But, were these ever “game changing”?

To be “game changing” a weapon or technology must be capable of completely changing the way war is fought or have the potential to substantially alter the results of a conflict. This isn’t a process of evolution; this is revolution, forcing an adversary to adapt suddenly to the new reality the “game changing” weapon brings. Otherwise, any significant improvement would be “game changing.” However, advances are rarely sudden, complete or limited to one side.

Chariots allowed mobile warfare. They were basically the first tanks. However, like tanks they were limited in where they could go, and couldn’t help in a siege or other aspects of ancient warfare. In places where they were effective, both sides would attempt to use them. If one side didn’t, it wasn’t as much game changing as the fact that the better equipped side enjoys advantages over the lesser (more on that later). The English longbow, famous at Agincourt and other battles, was not dramatically superior to crossbows of the era, or even superior to the muskets that replaced it. Massed crossbow or musket fire would have been just as effective against mounted knights. The advantage the English enjoyed was a pool of trained longbow men. The employment of the longbow was not sudden, unexpected, revolutionary, or more effective than other options of the era.

Gun powder weapons allowed greater striking power and, more importantly, did not require the dedicated skills needed for longbows or other previous weapons. (Admittedly they were more costly, always a factor in weapons acquisition.) Their introduction was not sudden, and slowly changed tactics. Instead of massed archers and crossbowmen, massed musketeers were fielded. It was not until rifling came about that tactics changed from massed formations of archers or musketeers to individual riflemen dispersing. Cannons slowly developed in accuracy and power, and castles with high walls were replaced by forts with sunken walls protected by a glacis from direct fire. This style of fortification remained until effective aerial bombardment made fixed fortifications obsolete. That change took about 400 years.

Gunpowder weapons have remained relatively unchanged in principle for centuries. Size, rate of fire, accuracy, and other dramatic improvements have been made, and tactics slowly adapted, just as games slowly adapt as rules are modified or players become better. Richard Gatling hoped his new rotary cannon would be so effective that it would discourage large scale battles and help end war. Regrettably, the Gatling gun did not change the game in that way.

Steam power freed warships from the wind but the tactics of sea combat remained the same, such as exchanging broadsides, preferably when the enemy cannot. Freedom from the wind was replaced by being enslaved to a logistics structure to provide the fuel needed.

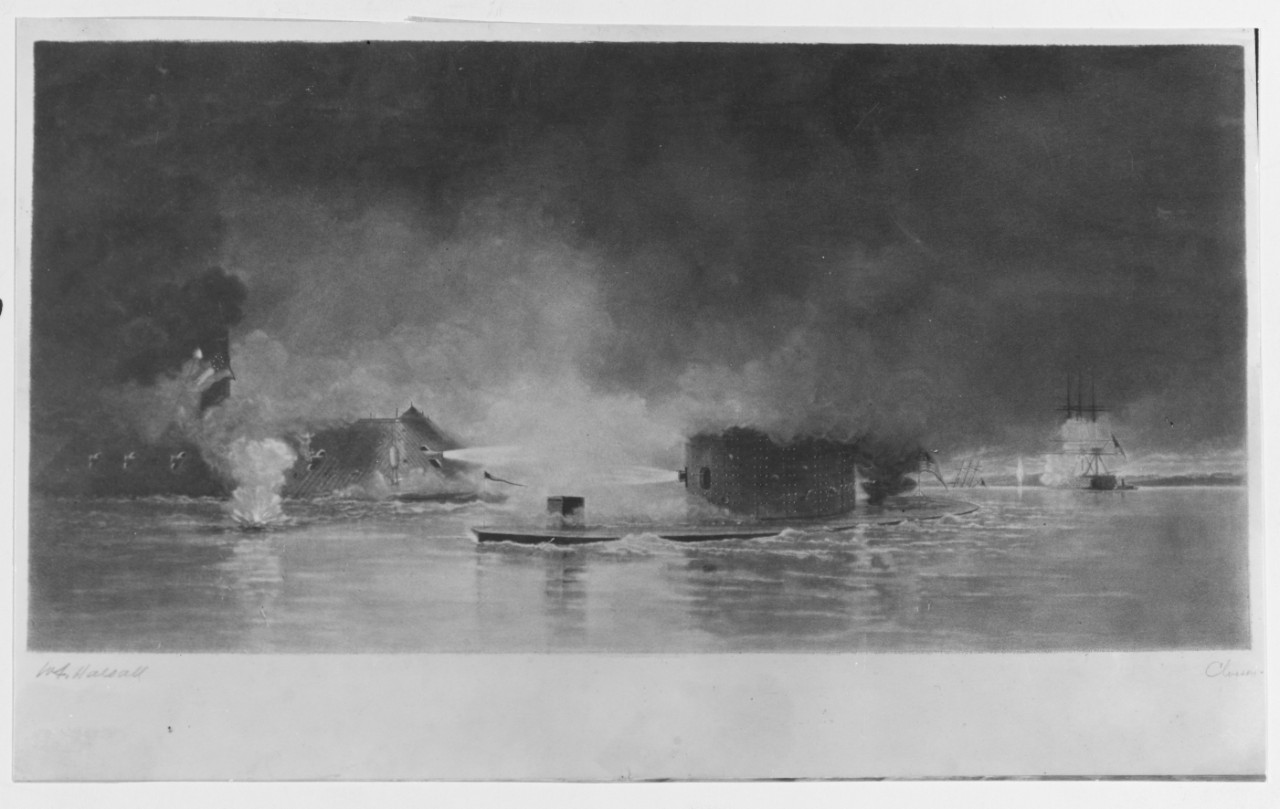

As offensive weapons improved, personal armor was generally phased out. Ships, in turn, became armored. CSS VIRGINIA and USS MONITOR dueled in Hampton Roads, but while signaling a change in the nature of war at sea, the ships did not decisively change the nature of the war or secure victory. Other nations already possessed armored ships. Unarmored ships continued to deploy in fleets decades later, and now armor is rare on ships once again as the power and precision of modern ordnance seems to have rendered it obsolete, a process that took about 100 years.

While Alfred Noble hoped that nations would recoil in horror from the efficacy of modern explosives, ending warfare, his invention of dynamite and the evolution of explosives didn’t have the effect he hoped. Powerful explosives changed the nature of warfare some, but didn’t eliminate it. The proliferation of heavy artillery, chemical weapons and machine guns during World War I wasn’t a game changing event either. Similar weapons have been employed in wars before and since. Against colonial foes unable to respond in kind, the brutal effectiveness of such weapons had already been demonstrated. In World War I, the opposing sides didn’t adapt rapidly to the increased lethality and lost thousands as a result. Did these weapons change the game? No. What resulted were static periods allowing both sides to besiege each other’s trench works. Massed infantry attacks against fortifications produced high casualties in wars long before World War I, and would again, as in the Iran-Iraq war.

At sea, the submarine became the new commerce raider, using an underwater approach instead of a false flag to approach an unsuspecting victim. The advent of unrestricted submarine warfare temporarily shocked military consciousness (before the war, the British Admiralty considered it unthinkable) but did not alter the war and it became just a part of World War I and II. At the end of World War II, Germany produced and employed the first ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, remote controlled aerial guided bombs and jet fighters. These were revolutionary weapons, for which the allies had no ready counter, but they did not snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.

Theorists like Douhet predicted that control of the air, and the strategic bombing it allowed, would decide all future wars, a view firmly embraced by the US Army Air Corp (fledgling US Air Force). Sustained bombardment of England by Germany, and then Germany by the Allies, did not decisively secure victory; nor did the air supremacy of the UN forces over Korea, nor French forces in Vietnam and Algeria. Over the skies of Vietnam, the US began employing the first precision guided weapons and were able to hit targets far more efficiently and with less collateral damage during the Linebacker campaign, as compared to Rolling Thunder or World War II bombing campaigns. The US and its allies were even more effective and proficient with these weapons during Desert Storm, but they simply allowed more strategic control from the air, which ground forces took advantage of just as they had in the early days of aviation. Jet aircraft, heavy intercontinental bombers, and precision guided weapons did not change the game enough to guarantee the success of the side that had them.

Similarly, the advent of nuclear weapons produced a more efficient way to bombard areas, but its political taboo, like that of chemical weapons, has thankfully prevented its use again. Did nuclear weapons change war? Many wars have been fought since 1945, and nuclear powers have considered using their arsenal but have not. One consideration was the political taboo of using them, but another was that they were not considered to be effective given the nature of the wars in Korea, Algeria, Vietnam and elsewhere. If the weapon is not considered more effective than conventional options, can it be considered game changing?

As has occurred in the past, media, think-tanks, and weapons designers label new weapons and tactics as potentially “game changing.” In many ways, cyber is electronic warfare by a new means. Cruise and ballistic missiles are one way bombers, or perhaps more accurately, very expensive and sophisticated artillery shells. Japan’s World War II Kamikaze’s were basically human-guided anti-ship missiles. Rail guns or lasers may slowly displace powder guns, but as with the bow and arrow being displaced by less efficient muskets and finally by very efficient repeating weapons, it will be a gradual process and the nature of conflict will evolve rather than suddenly change in response to a singular weapon or event.

“Game changing” weapons may seem to upset the balance at first, but a closer examination shows they are simply part of the evolution of warfare. They do not appear as suddenly or perform as effectively as the hype around the name implies. Tactics may change in response, and in this way the game is changed. However, the nature of war and strategy remains stable, despite new tools of the trade. The art of war, the vital game of life and death of a state, remains the same.